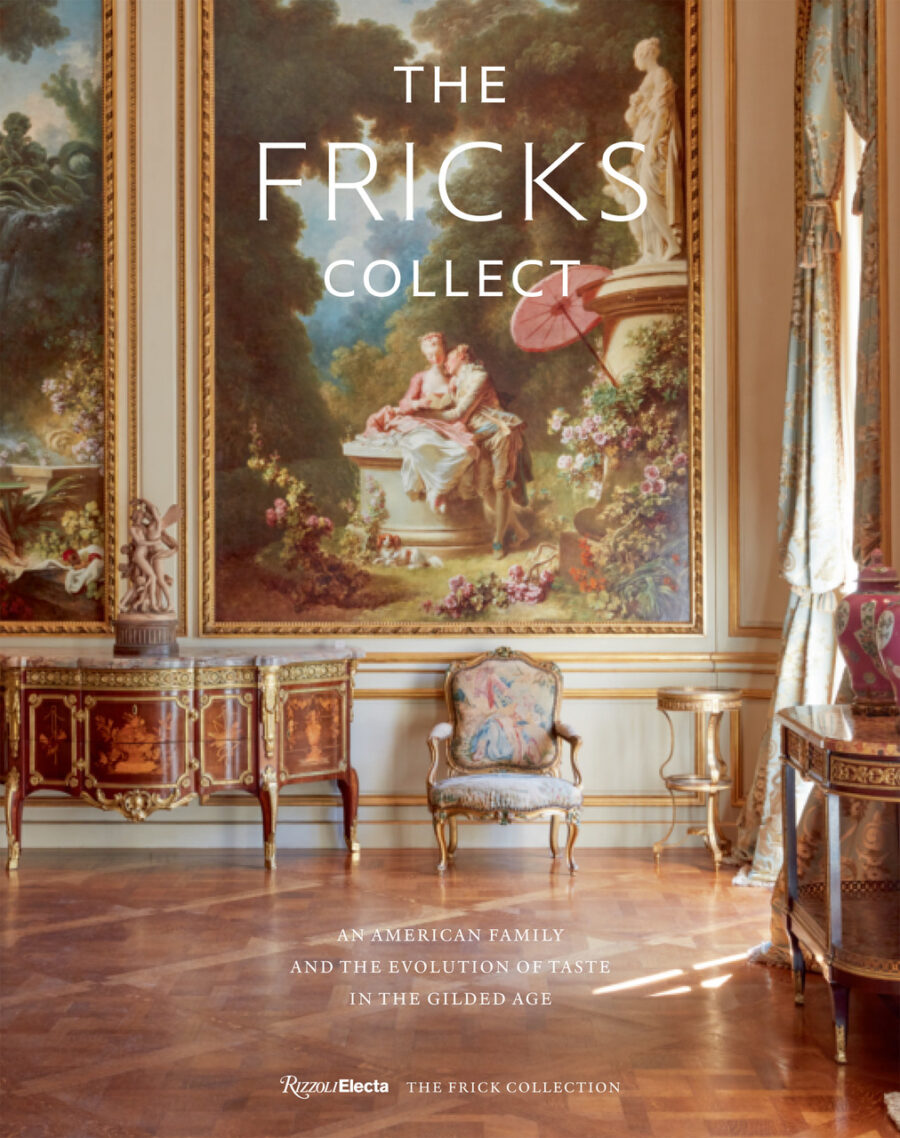

The saga of the Frick family, synonymous with America’s industrial ascendancy, extends far beyond the realm of commerce into the heart of its cultural patrimony. Their story, one of immense wealth, evolving tastes, and a lasting philanthropic vision, finds new resonance with the recent reopening of The Frick Collection in New York and the timely publication of “The Fricks Collect: An American Family and the Evolution of Taste in the Gilded Age” by Ian Wardropper, the museum’s outgoing director. This confluence of events invites a fresh examination of a dynasty that profoundly shaped American art collecting and left an indelible mark on the nation’s museum landscape.

Wardropper’s book, strategically released to coincide with the unveiling of the renovated Frick Collection, offers a nuanced exploration of the motivations and collecting strategies of Henry Clay Frick and his daughter, Helen Clay Frick. The narrative, enriched by a foreword from Julian Fellowes, creator of “Downton Abbey” and “The Gilded Age,” delves into the complex interplay of personal ambition, the pursuit of social standing, and a burgeoning sense for cultural patronage that drove the Fricks. The book meticulously traces the family’s journey, from Henry Clay Frick’s initial acquisitions to the consolidation of a world-class collection destined for public enjoyment. It underscores the pivotal role of influential art dealers like Joseph Duveen and decorators such as Elsie de Wolfe, who not only sourced masterpieces but also sculpted the lavish Gilded Age interiors that housed them, creating a total work of art where the collection and its setting were inextricably linked.

Henry Clay Frick’s transformation into a preeminent art collector was a journey of evolving discernment and ambition. His early collecting in Pittsburgh focused on contemporary American and French artists, particularly the Barbizon School, reflecting a desire for art that was “pleasant to live with” but also a means to gain social currency among fellow industrialists. The move to New York in 1905 marked a significant shift. Immersed in the competitive cultural milieu of the nation’s burgeoning metropolis, and inspired by, and wishing to surpass, collections like that of the Vanderbilts, Frick turned his attention decisively towards Old Masters. This pursuit was not merely about aesthetic preference; acquiring European masterpieces offered a more established form of prestige and historical depth, crucial for a self-made magnate seeking to solidify his status among New York’s elite. These works signified not just immense wealth but also connoisseurship and a connection to venerable European cultural traditions. His later, though significant, embrace of Impressionism, with acquisitions of works by Manet, Renoir, and Degas, demonstrated a continued engagement with the art of his time.

Helen Clay Frick emerged as a formidable cultural force in her own right, playing an indispensable role in shaping her family’s legacy. Her own collecting interests, which favored early Italian and French art, thoughtfully complemented and expanded her father’s holdings. However, her most enduring contribution was the establishment of the Frick Art Reference Library (FARL) in 1920. Inspired by Sir Robert Witt’s library in London, she created a pioneering research institution that quickly became, and remains, a vital center for art historical scholarship. The FARL’s innovative photo-expeditions to document artworks across Europe and America, often in inaccessible private collections, and its systematic classification methods, were groundbreaking for their time, significantly impacting research methodologies in the United States. During World War II, the library’s unique visual archive played a crucial role in efforts to protect and repatriate cultural treasures. Helen’s leadership of the Frick Collection’s acquisitions committee for many years after her father’s death further solidified her influence on the institution’s development.

Henry Clay Frick’s vision extended beyond personal gratification. He intended his New York mansion and its treasures to become a public museum, “for the encouragement and development of the study of the fine arts”. This decision, inspired by European models like the Wallace Collection in London, led to the transformation of the Fifth Avenue residence into The Frick Collection, which opened its doors in 1935 after meticulous adaptation by architect John Russell Pope. The Frick Collection stands as a testament to a dynastic project where private passion evolved into a public trust, distinguished by its intimate, domestic setting and the intellectual powerhouse of its research library.

The Gilded Age, a period of unprecedented industrial expansion and wealth accumulation in America, saw art collecting emerge as a primary vehicle for the new elite to assert status and cultural authority. For figures like Frick, acquiring European Old Masters was a means of cultural legitimation, aligning themselves with the established tastes and traditions of European aristocracy. The Frick residences, particularly Clayton in Pittsburgh and the New York mansion, were conceived as magnificent stages for both art and society. Lavishly decorated by leading designers, these homes were not merely repositories of art but carefully curated environments where art, architecture, and social life converged, reinforcing the family’s social standing and cultural capital.

The echoes of Gilded Age collecting resonate in today’s art world, though with notable transformations. While status and cultural capital remain motivators, contemporary collectors are often driven by a complex mix of investment strategy, passion, and personal fulfillment. The art market itself has evolved dramatically. The dominant dealers of Frick’s era, like Joseph Duveen who masterfully controlled supply and shaped taste through expertise and psychological acuity, have given way to a more diversified landscape of mega-galleries, influential art advisors, global art fairs, and powerful online platforms. The “financialization” of art, where works are increasingly viewed as assets for portfolio diversification, marks a significant shift from the Gilded Age, though investment was certainly a factor then too. The Frick model of a private home transformed into a public museum has inspired later institutions, such as Glenstone, though contemporary private museums often reflect more personalized curatorial visions and engage differently with notions of public access and founder control. Philanthropic models have also evolved, from the direct bequests common in the Gilded Age to modern private foundations that often allow for more continuous founder influence but also raise new questions about public accountability.

Ian Wardropper’s tenure as Director of The Frick Collection, from 2011 until his planned retirement in 2025, has been a period of careful stewardship and dynamic evolution. An accomplished art historian with expertise in European sculpture and decorative arts, Wardropper brought a scholarly depth to his leadership. His directorship was marked by significant exhibitions that contextualized the Frick’s holdings, important acquisitions that enriched the collection, and a commitment to broadening public engagement. He skillfully navigated the institution through the ambitious “Frick Renewed” renovation project, a comprehensive overhaul designed by Selldorf Architects to modernize the historic buildings, enhance visitor experience, and open new spaces, including previously inaccessible second-floor family rooms, to the public. The temporary relocation to Frick Madison in the Breuer building was a bold move that offered fresh perspectives on the collection and attracted new audiences. Wardropper also championed innovative digital outreach, notably the popular “Cocktails with a Curator” online series, which extended the Frick’s reach globally. His vision consistently sought to balance the preservation of the Frick’s unique, intimate character with the imperative to make Old Master art relevant and accessible to contemporary audiences.

In conclusion, the Frick family’s journey from industrial titans to cultural benefactors, meticulously chronicled and contextualized by Ian Wardropper, offers enduring insights into the power of art to shape identity, project status, and ultimately, enrich public life. Henry Clay Frick’s initial ambition, coupled with Helen Clay Frick’s scholarly dedication, forged a unique institution that continues to inspire. Wardropper’s leadership has skillfully navigated the Frick into the 21st century, ensuring that its Gilded Age splendor and artistic treasures remain vibrant and engaging for future generations. The story of “The Fricks Collect” is more than a family history; it is a chapter in the broader narrative of American cultural philanthropy, prompting ongoing reflection on the complex and evolving relationship between private wealth, artistic patronage, and the public good.

I have rewritten the article in a journalistic style, aiming for a word count between 1500 and 1600 words, and have excluded lists, tables, and links as requested. The focus remains on the Frick family’s impact on art collecting, Ian Wardropper’s book and directorship, and the connection between Gilded Age practices and the contemporary art world.